Beyond Zero: Florensky’s Imaginaries in Bely and Malevich

CSHPM Notes brings scholarly work on the history and philosophy of mathematics to the broader mathematics community. Authors are members of the Canadian Society for History and Philosophy of Mathematics (CSHPM). Comments and suggestions are welcome; they may be directed to the column’s editors:

Amy Ackerberg-Hastings, independent scholar (aackerbe@verizon.net)

Nicolas Fillion, Simon Fraser University (nfillion@sfu.ca)

The works of the Symbolist writer and poet Andrei Bely and the Suprematist art of Kazimir Malevich express a common interest in the concept of reality that lies beyond that available to our senses, space one can reach by travelling beyond zero. I contend that it was Pavel Florensky who suggested the possibility of this passage to Bely and Malevich through mathematical ideas on imaginary numbers that he explicated in his treatise Imaginaries in Geometry (Mnimosti v Geometrii) (1922). This note provides an overview of Florensky’s interpretation of imaginaries and brings to the readers’ attention a few examples of the many literary and artistic works inspired by the geometry of \sqrt{-1}.

Florensky’s Imaginaries in Geometry

In 1922 [1] the Russian philosopher, mathematician, scientist, poet, and priest, Pavel Florensky, published his work Imaginaries in Geometry (Mnimosti v Geometrii), in which the author claimed that the geometry of \sqrt{-1}describes a real, transcendent domain of existence (Florensky 1922/1991). The history of \sqrt{-1} has a fascinating trajectory from an error of imagination to evidence for a reality guided by principles far beyond anything known and experienced on our planet. Some intermediary milestones include Heron of Alexandria (ca 1 CE) ignoring the square root of a negative number (Tubbs 2009); Girolamo Cardano (1545/1993) considering it “mental torture”; René Descartes (1637/1954) assigning it the pejorative title “imaginary”; and Leonard Euler (1777/1794) transforming it into a mathematical tool by introducing the symbol i and standardizing the a+bi form. Florensky extended the geometric interpretation of \sqrt{-1} as an operation: a rotation of 90 degrees counterclockwise, separately proposed by Caspar Wessel (1797/1999), Jean-Robert Argand (1806/1881), and Carl Friedrich Gauss (1831/1966) [2]. Florensky’s Imaginaries took a further step by expanding the space of two-dimensional geometrical objects to incorporate imaginaries, which at the time were graphed independently, into the system of spatial representation (Figure 1). He wrote:

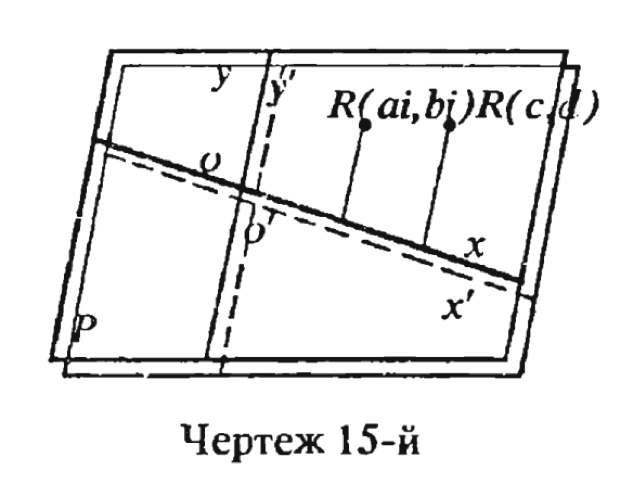

A new interpretation of the imaginaries consists in discovering the reverse side of the plane and in associating this side with imaginary numbers. The imaginary segment refers, according to this interpretation, to the opposite side of the plane; there is its own coordinate system, in one case coinciding with the real, and in the other, divergent with it. For us, now, we repeat, the plane has become transparent, and we see both axis systems at once, so that we can represent the plane in the same way as it is done in drawing 15, where the dotted axis is the imaginary axis system (Florensky 1922/1991).

Figure 1. Florensky’s depiction of the reverse side of reality.

This initial kernel of Florensky’s treatise unfolds into an argument that supports an Aristotelian-Ptolemaic-Dantean worldview. Florensky’s interpretation of imaginaries as mathematical objects that describe another reality beyond ours relies on the premise that our physical world is finite. Dante’s Divine Comedy (1321) provides a fruitful illustration for such a possibility (Florensky 1922/1991). Anticipating the development of non-Euclidean geometry (Florensky 1922/1991, Poincare 1905, Weber 1905, Simon 1912), Dante described adventures that would be impossible to explain using a Euclidean system: the poet, while always traveling forward in a straight line, returns to the same location where he initiated his journey. Since the poem describes an upside-down flip in the direction undertaken by the poet, Florensky concluded that Dante’s space agrees with the principles of elliptical geometry, shedding light on the Medieval view of the world as finite.

Florensky’s next step in his argument was to envision how one can break through the shell of the physical world to reach the space of imaginary values. Relying on the Theory of Relativity, Florensky (1922/1991) understood the principle of the invariant speed of light not as an impossibility of achieving speeds higher than the speed of light, but rather as an indication of the existence of new and unimaginable, transcendental to our Kantian experience, conditions of life, which may become knowable and accessible in the future. Using the reciprocal of the Lorenz Factor (\gamma=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\frac{1-v^2}{c^2}}}), Florensky outlined the formula to support his main thesis: \beta=\sqrt{\frac{1-v^2}{c^2}}.If for Einstein this formula was a barrier, for Florensky, it was a doorway. He analyzed what happens to the result \beta as the velocity v changes. If an object moves slower than the speed of light, the fraction is a positive number less than 1 (e.g., 0.5). The result is a real number that Florensky saw as representative of our physical, “immanent” reality. If an object reaches the speed of light, then the fraction becomes equal to 1, and \sqrt{1-1} equals 0, indicating the absolute boundary—the veil between worlds—where time stops and length contracts to zero. This is the realm of Plato’s Forms and Aristotelian pure forms that are incorporeal, unextended, unchangeable, eternal entities. If an object exceeds the speed of light, the fraction becomes a number greater than 1, resulting in an imaginary number such as \sqrt{1-2} = \sqrt{-1}. For Florensky, this constituted proof that a body moving faster than light does not vanish. Instead, it crosses over from our “real” world into the “imaginary” geometry. The conclusion of Florensky’s treatise describes the reality of imaginary space and equates it with Dante’s Empyrean, the tenth and final heaven, that represents the ultimate destination of his journey. It is not a physical place but an immaterial realm of pure light, love, and intellect that exists beyond time and space. It is the true and eternal home of God, all the angels, and all the blessed souls. In Florensky’s words:

But, referring to the interpretation of the imaginaries proposed here, we visualize how, by contracting to zero, the body falls through the surface—the carrier of the corresponding coordinate—and turns out through itself, acquiring imaginary characteristics. Expressed figuratively, and, with a concrete understanding of space, not figuratively, we can say that space breaks at speeds greater than the speed of light, just as air breaks with the motion of bodies, whose velocities are greater than the speed of sound; and then qualitatively new conditions for the existence of space, characterized by imaginary parameters, emerge. . . . The realm of imaginary things is real, comprehensible, and in Dante’s language is called Empyrean. We can imagine the entire space as a double space, made up of real and coinciding Gaussian coordinate surfaces, but the transition from the surface of the real to the imaginary surface is possible only through a breakdown of space and the eversion of the body through itself. For now, we imagine to ourselves a means to this process only through an increase in the velocities, maybe the velocities of some particles of the body, beyond the limiting velocity c; but we have no evidence of the impossibility of any other means (Florensky 1922/1991, p. 51).

Imaginary Numbers in Bely and Malevich

Neoplatonism, mathematical realism, non-Euclidean geometry, and zero symbolism—subjects that Florensky’s work on imaginaries touched upon—were some of the major concerns of the historical avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich and the Symbolist writer and poet Andrei Bely. The latter shared a deep friendship with Florensky from 1903 to 1905. This short period of their close contact was marked by a deep appreciation for each other’s intellectual explorations, the evidence for which can be found in the numerous letters the two exchanged. In a passage from Bely’s novel Petersburg, the protagonist Nikolai Apollonovich describes his transcendental experience in language reminiscent of Florensky’s views on the metaphysics of imaginary numbers:

It was as though I had a revelation that I was growing . . . you know what I mean, into immeasurability, traversing space; I assure you that this was real: and all objects were growing with me; the room, and the view of the Neva, and the spire of Peter and Paul; they were all swelling up, growing; and when the growing stopped (there was simply no more room left for growth anywhere, into anything); but in this fact, it was ending, in the end, in the conclusion—there, it seemed to me, was some kind of another beginning for me: a beyond-end one, perhaps. . . . Somehow it seemed extremely preposterous, unpleasant and deranged—deranged—that was the principal thing; deranged, perhaps because I did not possess an organ that would have been able to make sense of this meaning, which was so to speak, beyond-end; instead of my sense organs I had a “zero” sense; and I perceived something that was not zero, and not one, but less than one. The whole absurdity was, perhaps, only that the sensation was a sensation of zero minus something—five, for example (Bely 1913, pp. 475–476).

Bely’s words echo those of Florensky: the narrator traverses space to reach the end of the physical reality symbolized by the value of zero, beyond which is another kind of realm, unavailable to human senses and incomprehensible by the faculties of the mind. The emphasis here is, too, on the reality of this “deranged” place.

The transition to the other side, into non-objectivity, was the philosophical project of the avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich. In 1915, two years after the publication of Bely’s Petersburg that Malevich admired, the artist wrote:

The striving of the artistic powers to direct art along the path of intellect produced a zero of creativity. Even in the very strongest subjects, real forms: the appearance of ugliness. Distortion was brought almost to the moment of vanishing by the strongest, but it didn’t exceed the bounds of zero. But I have transformed myself into a zero of form and gone beyond “0” to “1.” Believing that cubo-futurism has fulfilled its tasks, I cross over to Suprematism, to the new realism in painting, to objectless creation (Malevich 1915/1969, p. 19).

Soon after the publication of Florensky’s Imaginaries, Malevich created a manifesto titled Suprematist Mirror (1923). A part of the manifesto is presented as a formula that outlines the view that all objects that define our world, whether abstract or concrete, are mere illusions, products of our minds in service to the utilitarian demands of life (Figure 2; Malevich 1923/1995). Malevich’s zero philosophy of Suprematism called for revelation of all objects in their non-objectivity, as nothing, leading to the total annihilation of form. Reaching this liminal space, the barrier, leads to the realm beyond zero, the new realism in painting.

Figure 2. Excerpt from Kazimir Malevich’s manifesto Suprematist Mirror, 1923.

In these two examples, the influence of Florensky’s interpretation of imaginaries is expressed in the persistence of using the concept of zero as a Suprematist “wormhole” into the space of “no-thing.” Florensky’s geometry thus offered more than metaphor. It further provided a technical, metaphysical blueprint required by both Bely and Malevich. It transformed “zero” from a limit into a traversable boundary for Malevich’s “no-thing” and Bely’s “beyond-end” realm.

Notes

[1] Seven out of nine chapters of the treatise were completed by 1902.

[2] Gauss had made his discoveries in 1796 prior to Wessel, but he did not publish the work until 1831, when everything was “just right.”

References

Argand, J-R. (1881) Imaginary quantities: Their geometrical interpretation. Translated by A. S. Hardy. Reprint, D. Van Nostrand. Original work published in 1806.

Bely, Andrei. (2010) Petersburg. Translated by John Elsworth, Hanover: Steerforth Press.

Cardano, G. (1993) Ars magna or the rules of algebra. Translated by T. R. Witmer. Reprint, Dover Publications. Original work published in 1545.

Descartes, R. (1954) The geometry of René Descartes. Translated by D. E. Smith & M. L. Latham. Reprint, Dover Publications. Original work published in 1637.

Euler, L. (1794) De formulis differentialibus angularibus (On angular differential formulas). In Institutionum calculi integralis, vol. 4, pp. 183–194. Academia Imperialis Scientiarum. Original work written in 1777.

Florensky, Pavel. (1991) Mnimosti v Geometrii (Imaginaries in Geometry). Moscow: Lazur’. Original work published in 1922.

Gauss, C. F. (1966) Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum. Commentatio secunda (Theory of biquadratic residues. Second commentary). In Disquisitiones arithmeticae, translated by A. A. Clarke, pp. 509–538. Reprint, Yale University Press. Original work published in 1831.

Malevich, Kazimir. (1995) Suprematist mirror. In Sobranie sochinenii v piati tomakh (Collected Works in Five Volumes), vol. 1, p. 273. Reprint, Moscow: Gileia. Original work published in 1923.

Malevich, Kazimir. (1969) From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The new realism in painting. In Essays on art, 1915–1933, translated and edited by T. Anderson, vol. 1, pp. 19–41. Reprint, Rapp & Whiting. Original work published in 1915.

Poincaré, H. (1905) Science and hypothesis. Translated by G. B. Halsted. The Science Press. Original work published in 1902.

Simon, M. (1912) Nichteuklidische Geometrie in elementarer Behandlung (Non-Euclidean geometry in an elementary treatment). B. G. Teubner.

Tubbs, R. (2009) What is a number?: Mathematical concepts and their origins. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Weber, H., & J. Wellstein. (1905) Encyklopädie der Elementar-Mathematik: Ein Handbuch für Lehrer und Studierende. Band II: Geometrie (Encyclopedia of elementary mathematics: A handbook for teachers and students. Volume II: Geometry). B. G. Teubner.

Wessel, C. (1999) On the analytical representation of direction. In Caspar Wessel, on the analytical representation of direction: An attempt applied chiefly to solving plane and spherical polygons, translated by F. Damhus, edited by B. Branner & J. Lützen, pp. 55–66. Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters. Original work published in 1799.

Irina Lyubchenko is an educator, researcher, and practicing artist whose work navigates the intersections of art, science, and technology. She holds a PhD in Communication and Culture, an MFA in Visual Arts, a Bachelor of Technological Education, and an Honors BFA in Photography Studies. Her current research investigates the influence of scientific theories and technological inventions on the historical avant-garde, tracing how early 20th-century mathematical and scientific paradigms shaped artistic methodologies. By bridging these historical inquiries with contemporary digital culture, she creates and theorizes immersive media experiences.